In the last several years, surveys have found that almost half of American adults are trying to lose weight.

So chances are high that weight loss has been a goal of yours sometime in the recent past.

You may have attempted to lose weight by cutting calories, which makes sense. Most people understand that if you consume fewer calories than you burn each day, you’ll lose weight.

A question many people don’t consider, however, is the following:

What kind of weight am I losing?

Advertisement

You can lose:

- Muscle

- Body fat

- Bone mass

- Water

Using the scale in your bathroom only measures the total amount of weight lost.* It measures the force of gravity on your body.

(*Note: We know that some people own special bathroom scales that perform bioelectrical impedance and give you estimations of your body fat percentage and other cool information—we’ll talk more about that later!).

So let’s pause for a moment and really consider: why does our scale weight matter so much to us?

The real, ultimate goal is a certain “look”—a toned, fit body, regardless of what it weighs, right?

Advertisement

The scale can’t tell you if your clothes fit better and it definitely won’t tell you that you’re looking any better.

So let’s explore the possibility that there are other, more valuable ways than using your scale weight to measure progress and success when following a nutrition and/or fitness program. One of those ways is assessing changes in body composition.

What is body composition?

Your body composition refers to the amount of fat and fat-free mass (muscle, bone, and water) your body contains.

We focus on body composition because our goal is bigger than simply achieving a lower number on the scale.

We want to add lean muscle tissue and reduce the amount of body fat that we carry, which helps us achieve the defined, fit, toned look that you may be seeking.

Advertisement

Why is this the case?

Well, you may have heard the saying that “muscle weighs more than fat.” However, this saying doesn’t quite get it right. One pound of muscle and one pound of fat technically do weigh the same amount (one pound).

But two things that weigh the same amount can be very different in size. One pound of goose feathers is going to take up a great deal more space than a dumbbell that weighs one pound.

This applies to body fat and muscle as well. One pound of muscle is quite a bit harder and denser than a pound of body fat. They weigh the same, but their size is different.

Consider how this applies to your body composition. If you gain 5 pounds of muscle and drop five pounds of body fat, your scale weight will be exactly the same. But in your clothes and in the mirror, you’ll notice a huge difference.

Advertisement

If all this is true, why should we use the scale at all?

How do we know if we’re truly making progress without it?

The scale is a tool.

Like any tool, it does serve a purpose and it can be useful in your journey toward your fittest, healthiest self.

It’s a tool in the same way that a tape measure is a tool to measure the circumference of your chest, hips or waist.

Advertisement

However, unlike a tape measure, many people have a strong emotional attachment to the scale. They see the scale number as proof of whether they have been “good” or “bad.” For many people, five seconds on the bathroom scale in the morning can ruin their entire day.

Using the scale the wrong way

Let’s see if you can relate to this story about the scale involving our friend “Jane.”*

“Jane” was a real client with Working Against Gravity, with her name changed.

Jane was determined to lose weight. She felt uncomfortable in her skin and all her clothes felt tight.

Not knowing what else to do, she cut her calorie intake as much as possible. She was hungry and miserable, but she felt there was no other option.

Advertisement

Jane felt so exhausted from the low calories that she could not find the energy to exercise, so she skipped her usual workouts that week.

After a solid week of white-knuckling her way through this plan, Jane went to weigh herself, excited to (hopefully) see a huge drop!

Her heart pounding, she stepped on the scale and—how could this be?! The scale went up by two pounds!

Jane was devastated and felt that her whole day was ruined. To comfort herself, she stopped at the local donut shop on the way to work—what did it matter, anyway? Her diet didn’t work. She felt like a failure.

Can you relate to Jane’s story? Have you ever stepped on the scale after working hard on a nutrition or fitness goal, only to find that your weight stayed the same—or worse, went up?

Advertisement

Our goal is to shift your perspective so that your understanding of changing your body is more all-encompassing.

We want you to realize that you can’t simply rely on the scale to give you a “report card” of whether your nutrition and fitness regime is effective or ineffective. There’s a lot more to it!

How much body fat can we actually lose in a week?

Here’s the reality: we can only lose about 0.5–1% of our body weight in true body fat per week.

If we lose much more than that, there’s a high chance its water weight (or worse, that some muscle has been lost too).

Advertisement

You might be wondering: but what about that time I went on a diet and lost 10 pounds in a week?

Well, some body fat was likely lost during that week—but chances are high that most of it was, unfortunately, water weight.

Water weight, both gained and lost, can make things very confusing for those of us monitoring changes in our body composition.

Losing water weight is like buffing your car. It makes the exterior look sleeker, but the changes are short-lived.

Rather than focusing on weight loss, the real goal for your journey should be to preserve as much muscle as possible, or possibly even gain some, while losing as much fat as possible.

Advertisement

Maybe that will lead to weight loss on the scale, but it might not.

Either way, you’re going to have a much-improved body composition.

You have likely heard the “rule” that gaining a pound requires consuming 3,500 calories. (That’s 3,500 calories above your maintenance-level calorie amount, i.e., the number of calories you need to stay the same weight.)

What this means is that, unless you ate many thousands of calories (say, 5,000 or 6,000) in a single day, you didn’t gain a pound of weight overnight.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, unless you ate nothing and did quite a bit of exercise, you can’t lose a pound of weight in a single day, either.

Advertisement

Those daily fluctuations on the scale are due to changes in water weight and the weight of the food sitting in your gut.

Using the scale the right way

Put simply: rather than worrying about those fluctuating daily scale amounts, you’re going to monitor scale trends over time. Here’s how:

We recommend a daily weigh-in, first thing in the morning, after you use the bathroom, before eating or drinking anything, without any clothing. Record the number and move on from it—we don’t care about a single day’s weight. Instead, you’re going to use the daily weigh-ins to generate an average for the week.

You can generate an average using an Excel or other type of spreadsheet, using the “average” equation function built into the software. Make sure to collect at least three weigh-ins from the week, hopefully under the same conditions each time (same time of day, same scale, etc.).

Once you have calculated the average weight, the goal is to compare it from one week to the next. When you use the average, it will “flatten out” those daily fluctuations that inevitably occur due to a long list of reasons (hormone changes, you ate something high in salt last night, you didn’t sleep well, etc.).

Advertisement

Okay, but the scale still causes me a lot of stress. Do I have to use it?

Sometimes tracking body weight is more stressful than it’s worth.

If you find that weighing yourself frequently is causing a lot of emotional turmoil, that’s okay—we recommend taking a break from the scale or getting rid of it entirely. There are many other ways to monitor changes in body composition that you’ll read about below. Our favorite is by using body circumference measurements and visual assessments (e.g., progress pictures).

Other ways of assessing progress beyond the scale

Now let’s dive into the other ways we can monitor and assess progress aside from your scale weight.

Many people wonder, what about measuring my body fat percentage? My gym (or my bathroom scale at home) has a machine that allows me to test it.

Advertisement

There are pros and cons to measuring body fat percentage (we discussed some of them in this article).

Put simply, the main issue with measuring your body fat percentage using a machine (such as an InBody or a DEXA scan) is that these readings are always estimates.

There’s no way to know a person’s exact body fat percentage.

You can click here to read about the bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), which is one common and popular way to measure body fat percentage. BIA is the method used in devices such as the InBody machine, which is featured in many gyms.

BIA measurements aren’t very accurate or reliable—however, they may be used to observe trends in body composition over time.

Advertisement

What about the “gold standard” for measuring body fat, the DEXA scan?

You may have heard of the dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan.

DEXA uses X-rays of two different energies to estimate your body fat percentage. DEXA is also used to assess bone density and provides detailed information about the bone, lean mass, and fat in each region of your body.

The main advantage of DEXA is that it’s more accurate than most other methods, including bioelectrical impedance.

However, even with this higher level of accuracy, there’s still a significant error rate for DEXA. Some experts suggest that the error rate means that DEXA is actually useless at the individual level (but useful for studying groups of people). This is because, when properly done, a DEXA assessment always has a ± 2% error rate for repeated body fat assessments in the same individual.

Advertisement

So a measurement of 18% body fat is actually a measurement of 16–20% body fat, which is a big range when we consider the fact that a solid rate of body fat loss for a given week is 0.5–1% of your total body weight.

Example of how inaccurate DEXA results can be problematic

Let’s say Jane got a DEXA scan on Sept. 1, at the beginning of her new nutrition program.

The machine gave Jane an inaccurate measurement of 22% body fat when she was actually at 24% body fat.

Jane worked really hard at her nutrition and training program for one month. She noticed some changes in how her clothes fit and friends commented on how she looked leaner and more defined.

Advertisement

She got another DEXA scan on October 1.

Jane’s nutrition and training programs have been effective, and she lost 2% body fat, bringing her to 22% body fat. Woo-hoo!

However, due to the error of the machine, Jane got a reading of 23% body fat (remember, the error rate is ± 2%)—which is 1% higher than her initial DEXA scan a month ago!

(Note: We are assuming that the lab technician conducting Jane’s test is very experienced, using research-grade equipment and standardized protocols. This isn’t always the case, which could further impact the accuracy of the results.)

This result left Jane feeling devastated and discouraged. A month of hard work appeared to have amounted to nothing—even though, in reality, her program was very effective. Jane ending up losing the motivation to keep going, and rather than continuing to make great progress, she stopped following her program.

Advertisement

That is not what we want to happen to you!

Machines that estimate your body fat percentage are generally unreliable and we don’t recommend using them as your main method of measuring progress. At best, these tests are uninformative and at worst they’re potentially harmful, as they may convince you that no progress is being made even when there are other signs of progress.

Taking progress photos

Visual progress assessments (including photos or even a video of yourself) are very helpful tools in your journey toward achieving your fittest body.

The only downside to progress photos is that they are subjective and qualitative. Most of us are quite hard on ourselves, so we might find it difficult to notice small changes in photos from week to week. (This is an instance where it’s very helpful to have a coach on your side.)

Advertisement

We also have some tips for taking great progress photos that show off your progress in the most accurate way:

- Take them with a light source facing you.

- Wear the same outfit or bathing suit each time.

- Take them first thing in the morning before eating, drinking or exercising.

The leaner you are, the easier it will be to see changes from week to week. Don’t be discouraged if you don’t see huge changes in your photos from one week to the next. Just like with assessments of your scale weight, look for trends over the span of multiple weeks.

Additionally, remember that if you have the goal of gaining lean muscle, this is a very slow process and you likely will not notice major muscle gains over the span of two to three weeks. This is especially true the longer you have been training.

When you’re aiming to gain muscle, it’s better to rely on improvements in gym performance (for example, increasing the amount of weight you can lift) as opposed to waiting for major changes to show up in your photos.

Body circumference measurements (the best option of all!)

Advertisement

Our favorite method for assessing changes in body composition is to measure the circumference of various areas of your body.

Why are circumference measurements so useful?

Because, as we know from the information above, scale weight changes on their own can’t tell us how much muscle we’ve gained or how much body fat we’ve lost. In other words, the scale can’t tell us how we look.

Plus, if you’re someone who isn’t necessarily overweight or underweight and you’re new to strength training, you might not see many changes in your scale weight (as you gain lean muscle mass and reduce your overall body fat).

This could become very frustrating for you, which is why tracking changes in your measurements can offer a major increase in motivation.

Advertisement

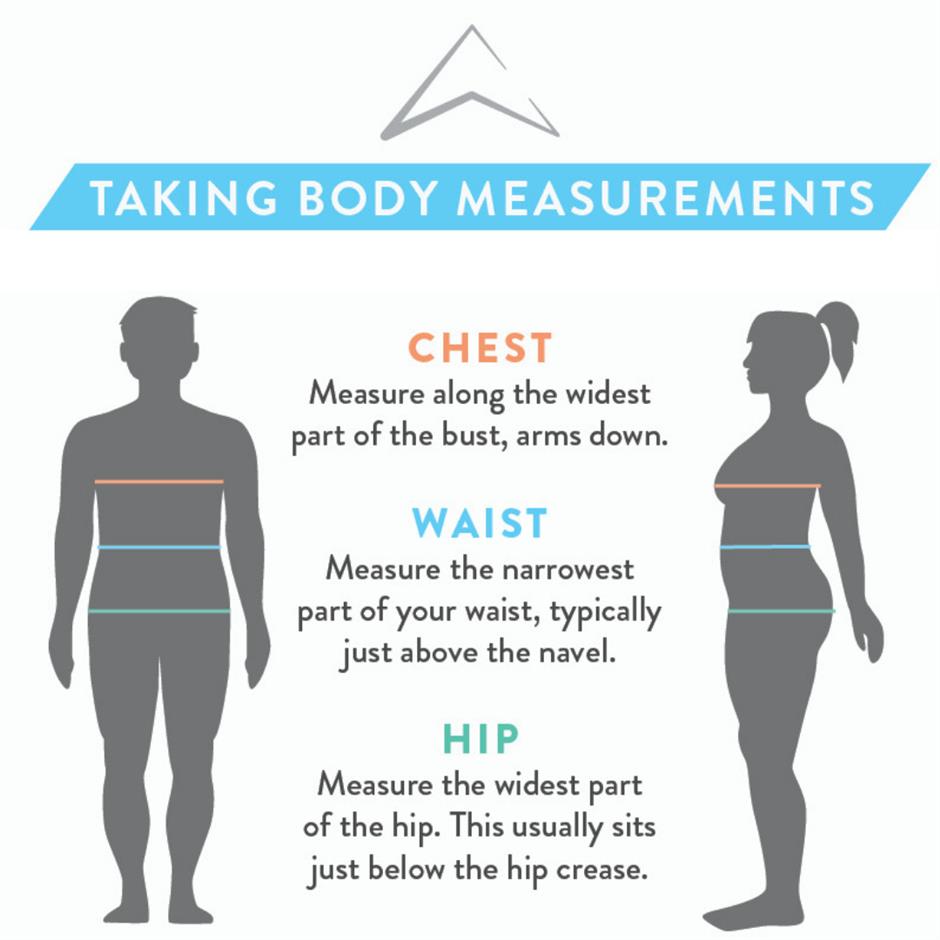

How (and where) to measure

You can measure your body circumference in as many as seven different places, including:

- Chest

- Each arm

- Waist (about 2 inches above your navel)

- Navel

- Two inches below your navel

- Hips

- Each thigh

However, if you don’t want to measure that many spots, it’s sufficient to measure your chest, waist, and hips.

Just like with scale weights, it’s important to keep these measurements as consistent as possible. We recommend measuring yourself once per week on the same day.

Advertisement

Also, similar to weight changes, don’t worry if the measurements show little change from one week to the next. You’re looking for trends over time.

What if I am a performance athlete—how should I use the scale?

Certain athletes compete in weight sports, like Olympic weightlifting or powerlifting, which means that, whether they like it or not, they must use the scale.

However, similarly, with people who do not compete in weight-class sports, the scale isn’t the only important measure of progress or success.

If you’re a performance athlete, the goal for you should be to find the right body composition that allows you to (sustainably) perform at your best, mentally and physically. This means that you don’t want to be so lean that it’s unsustainable and negatively impacts your performance, but you also don’t want to carry excess body fat that’s unnecessary for your sport. You’re seeking a “sweet spot.”

Advertisement

The magic of resistance training

We’ve talked a lot about the difference between losing weight on the scale versus losing body fat and gaining lean muscle (i.e., changing your body composition).

A very important piece of this equation is resistance training!

On your quest to achieve your fittest body, you may have been tempted to add cardio. After all, cardio burns lots of calories, and that’s our main goal, right?

Not exactly.

Weight training doesn’t burn as many calories as cardio, per session—this is true. However, weight training is far more effective than cardio at building muscle, and muscle burns more calories at rest than fat.

Advertisement

Weight training can help raise your resting metabolic rate (i.e., the number of calories you burn when you’re at rest—including when you’re asleep!).

In addition, strength training workouts burn calories for many hours following the session (far more than cardio workouts).

Also, many studies demonstrate the benefits of strength training for improving body composition.,

If you monitor your nutrition (for example, by using a program like Working Against Gravity), but don't participate in some kind of resistance training program, you may lose body fat, but you may not achieve the defined, toned look you are aiming for. Effective body recomposition requires both manipulation of your caloric intake and your output in terms of exercise.

Assessing progress and making adjustments

Okay, let’s say you’ve taken all the advice above. When is it time to determine whether the program is working, and how do you make that decision?

Advertisement

First of all, follow your program for two weeks before making any changes.

We recommend waiting this long because your first week, especially on a fat loss diet, may involve losing a significant amount of water weight and glycogen purely from your overall reduction in food intake.

Two weeks is typically enough time to see if your progress is trending in the direction you want.

Note: If you’re a woman and your period arrives somewhere in that two-week span, we recommend waiting one more week before assessing progress (due to menstrual-cycle water retention).

Okay, now it’s time to determine how things are going!

Advertisement

Let’s say you’ve done all the following steps:

- Took photos (or video) and measurements of your physique at the beginning of your program.

- Weighed yourself daily under the same circumstances each time.

- Did the math to calculate your average weekly weight for each of the last two weeks.

- Followed some kind of nutrition program (hopefully keeping track of your intake in some manner, such as tracking your food in an app).

The next question becomes, how do you know if it’s working?

We encourage you to assess all the indicators of progress that we’ve outlined in a sort of “meta-analysis.”

Let all of them together paint a picture of what’s changing (or not changing) with your body.

Here are some possibilities you might encounter:

Advertisement

Perhaps your scale weight stayed the same over a span of two weeks, but your waist measurement dropped by several centimeters. That is progress and a sign that you lost body fat!

Or maybe you can’t see a difference when comparing your initial photos to the current ones, but you were able to deadlift 10 pounds more this week than you did two weeks ago. That’s progress too! It shows that you gained strength and are increasing your lean muscle mass, which will make your metabolism faster.

Or perhaps you feel like nothing is changing with your body, but your friends at the gym commented that you’re looking fitter and more defined. You notice that your pants fit a bit looser. Those are very strong signs that you’ve lost body fat!

The biggest take-home message when it comes to the difference between losing weight and losing body fat (i.e., changing your body composition) is simply that it takes time. If you remain patient, consistent and objectively monitor your progress, the result will be worth it!

Ready to focus on fat loss but unsure where to start?

When it comes to losing fat (not just water weight), you need to find a nutrition plan that’s sustainable for you.

Advertisement

Like we mentioned, it’s scientifically impossible to actually lose pounds of fat overnight. So, in order to make a substantial change, you need a plan that you can continue following for a substantial amount of time.

After all, the main difference between a successful diet and an unsuccessful one isn’t the diet itself, but whether or not we can stick to it.

When you join Working Against Gravity, we pair you up with a (real-life) personal nutrition coach who works directly with you, providing you with the ultimate level of support and accountability.

Together, you’ll find which foods and strategies work best for you on an individual level—because helping you remain consistent is exactly what will help you reach your goals.

You’ll also join the #TeamWAG family, which is an entire online community in your corner 24/7 to cheer you on, share advice and keep you moving in the right direction!

Advertisement

References:

References

- Martin CB, Herrick KA, Sarafrazi N, Ogden CL. Attempts to lose weight among adults in the United States, 2013–2016. NCHS Data Brief, no 313. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018.

- Andrea C Buchholz, Dale A Schoeller, Is a calorie a calorie?, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 79, Issue 5, May 2004, pp. 899S–906S, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.5.899S.

- Kubala, J., RD. (2018, August 5). Body Recomposition: Lose Fat and Gain Muscle at the Same Time. Retrieved July 20, 2019, from https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/body-recomposition.

- Helms, E., Morgan, A., & Valdez, A. (2019). The Muscle & Strength Pyramid: Nutrition (2nd ed.), p. 54.

- Ibid, p. 180.

- Benn, Y., Webb, T. L., Chang, B. P., & Harkin, B. (2016). What is the psychological impact of self-weighing? A meta-analysis. Health psychology review, 10(2), 187–203. doi:10.1080/17437199.2016.1138871

- Helms, et al., The Muscle, 77.

- Hind, K., et al., Interpretation of Dual Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry-Derived Body Composition Change in Athletes: a Review and Recommendations for Best Practice. J Clin Densitom, 2018. 21(3) pp. 429–43.

- Helms, et al., The Muscle, p. 178.

- Feigenbaum, M & L. Pollock, Michael. (1999). Prescription of resistance training for health and disease. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 31. 38-45. 10.1097/00005768-199901000-00008.

- T. Lemmer, Jeffrey & Ivey, Fred & S. Ryan, Alice & Martel, Gordon & E. Hurlbut, Diane & E. Metter, Jeffrey & L. Fozard, James & L. Fleg, Jerome & Hurley, Ben. (2001). Effect of strength training on resting metabolic rate and physical activity: Age and gender comparisons. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 33. 532-41. 10.1097/00005768-200104000-00005.

- Schuenke, M.D., Mikat, R.P. & McBride, J.M. Eur J Appl Physiol (2002) 86: 411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-001-0568-y

- L Ballor, D & Katch, Victor & Becque, Motier & R Marks, C. (1988). Resistance weight training during caloric restriction enhances lean body weight maintenance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 47. 19-25. 10.1093/ajcn/47.1.19.

- Cava, E., Yeat, N. C., & Mittendorfer, B. (2017). Preserving Healthy Muscle during Weight Loss. Advances in Nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 8(3), 511–519. doi:10.3945/an.116.014506

Schedule a Free Intro Call

Working Against Gravity has led the macro tracking and health space for over a decade. Our team doesn’t just understand the science of nutrition—we’ve spent years mastering the art of tailoring it to fit your life. That means no cookie-cutter plans, just real strategies that have worked for over 30,000 people.

Schedule a free call with our team to learn how working with a 1-on-1 WAG coach will help you reach your goals.